Rosalie M. Ladova, 1863-1939

By Emma Florio, Special Collections Library Assistant

Content warning: this article includes names of historical institutions that contain outdated, harmful terms.

|

|

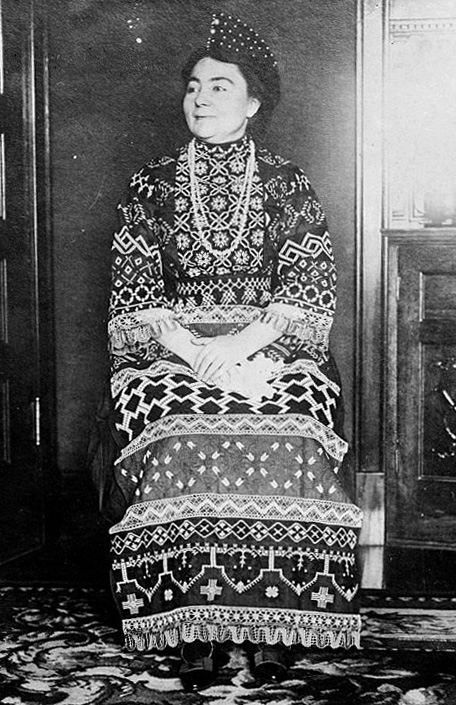

Ladova in traditional clothing, ca. 1910. Via Library of Congress.

|

Rosalie M. Ladova was born into a Russian Jewish family in 1863. At age 28 she immigrated to the United States and would eventually become naturalized as a citizen in 1904. She first settled in Milwaukee in the 1890s, where she worked as a practitioner of massage and “medical gymnastics,” a type of physical therapy that exercised the muscles.

By 1897 Ladova had moved to Chicago and enrolled at Northwestern University Woman’s Medical School. She earned her MD in 1898, along with a prize as the top student of the school. She completed an internship at Chicago’s Mary Harris Thompson Hospital, a hospital for women and children.

Early in her career, Ladova’s jobs included medical inspector for the Chicago Board of Education; a translator of medical texts, utilizing her knowledge of French, German, and Russian; an instructor for diseases of the chest, nose, and throat at Rush Medical College; and assistant physician in the chest, nose, and throat department at the Northern Hospital for the Insane in Winnebago, Wisconsin. This later job signaled a shift in her career, as she turned toward neurology and psychiatry. In the 1910s she worked at the Chicago Hospital for the Insane and the Women’s State Epileptic Colony in Michigan. She also wrote articles on topics ranging from aortic insufficiency to neurasthenia (a popular diagnosis at the turn of the 20th century for symptoms including physical and mental exhaustion).

Ladova also fought for women’s rights throughout her life. In 1902 she wrote an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association that called for equal, high-quality medical training for women as well as more opportunities for training in specialties like surgery, pathology, and bacteriology. She argued that women could accomplish anything their male counterparts could, including lab work, invasive surgery, and post-mortem dissections, and that they should not be limited by ideas of appropriate feminine behavior. She also supported women’s suffrage organizations and protested the American Red Cross’s discrimination against women surgeons who wanted to support the war effort during World War I.

|

|

Ladova in the bathing suit that got her arrested, from the Chicago Tribune, July 28, 1913.

|

In 1913, Ladova made headlines across the country for one particular protest on behalf of women’s rights. On July 27 of that year, she was arrested for disorderly conduct at Chicago’s 63rd Street Beach after removing her skirt and attempting to swim in bloomers. These baggy, knee-length trousers were seen as a symbol of the dress reform movement that advocated for more practical and comfortable clothing for women. By wearing them—and not the full-length skirt required for public swimming by city ordinances—Ladova sought to point out the double standard that allowed men to wear more revealing, and thus less cumbersome, clothing for swimming. When she appeared in court the next day, the judge dismissed the case against her, saying her outfit was “quite modest” and that “no one but a prude could object to it.”¹ By the next summer, the city had passed new ordinances that allowed women to wear bloomers while swimming.

Ladova continued to work into the 1930s, until she died in 1939. Her obituary in the Chicago Tribune described her as a “pioneer woman physician” and a “leader in the fight for women’s rights.” Despite her successful medical career and her other advocacy for women’s rights, she is best remembered today, in books, articles, and across the Internet, for her run-in with the law in the summer of 1913 that ended up changing the laws of Chicago.

Endnotes

1. Joseph Gustaitis, Chicago Transformed: World War I and the Windy City (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016), 172.

Updated: March 14, 2024